Disclaimer: you can also read this interview in Italian, here.

Today’s Guest of Honour, Bruce Heard, doesn’t need any presentation. Author and game designer since the Golden Age of BECMI D&D (Basic, Expert, Companion, Master and Immortals, the first version translated in italian), he is the person responsible for the development of the Mystara Setting, the Voyages of the Princess Ark series and the ambitious Rules Cyclopedia. He recently launched the excellent Calidar: In Stranger Skies, first volume of his brand new campaign setting. We are delighted to have this opportunity to interview Bruce exclusively for you, readers of Isola Illyon.

GAZ3, The Principalities of Glantri.

Tell us your story: how did you become lead designer and product manager for BECMI and Mystara products, and what did you do after TSR’s bankruptcy?

After working as a French translator for Basic and Expert modules, I moved on to administrate freelance acquisitions for the Games Division. This entailed selecting and hiring outside writers to design products that couldn’t be handled in-house. Basic/Expert wasn’t popular among TSR’s designers, at least not initially. In-house staff were more interested in working on AD&D projects at the time because that’s where public attention was. Therefore, leftover assignments became my responsibility. Political turmoil soon resulted in the departures of Gary Gygax and Frank Mentzer from TSR. The last remaining person directly involved with BECMI was me. It wasn’t long before I became the product’s “manager by default.” Since I did well in this function, the position became official over time.

TSR was very generous and trusting of its creative staff in that it permitted them to pick up freelance assignments over and above their normal in-house workloads. Fortunately, it worked out all right, for most. This option was available for me as well, so I was able to design several BECMI products, including the famous GAZ3 “Principalities of Glantri.” Likewise, the house periodical, “Dragon” Magazine, was actively seeking in-house contributions, which were well paid (their rates thirty years ago were as high or higher than most rates offered today by hobby gaming magazines). This allowed me the opportunity to develop the “Voyages of the Princess Ark,” a very popular series among the magazine’s readers.

After TSR’s flame was doused, I worked for different companies unrelated to the gaming industry. My attention was focused elsewhere, and honestly this made for a rather bleak existence. I did very little gaming and no writing until Janet, my fiancée, twisted my arm to get back into the arts. I felt incredibly rusty, but soldiered on. I managed a short story, which was published in an anthology, knocking off that stifling crust of mindless uncreativity accumulated over the years (“One tiny tale for a little book, one giant saga for Bruce!”) Janet and I tried our collective hands at writing novels. We finished two of them, which have been mothballed until such time we can release them on our own. That’s when I decided to go back to my roots, first Mystara and, in the face of WotC’s mental rigidity, Calidar.

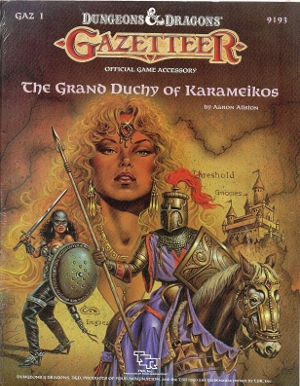

GAZ1, The Grand Duchy of Karameikos

How was a Mystara Gazetteer developed, and how much were you involved with the creation of Gazetteers you didn’t write personally?

I wanted accessories fleshing out the various realms of the Known World. Before coming to TSR, I used to run a Greyhawk campaign with my gaming buddies. To me, D&D had to be played in a fantasy world. BECMI had one, but it wasn’t developed beyond the few paragraphs in the Expert Set. So the decision was logical. I drafted the parameters for the new project, which became GAZ1 “Grand Duchy of Karameikos,” and expedited the contract to Aaron Allston, who did a fabulous job. I reviewed his work and was very satisfied. I promptly turned around and assigned follow-up projects, inviting big names such as Ken Rolston, Steve Perrin, and Jim Bambra, who all did excellent work. Aaron became a major contributor with such titles as the “Hollow World”, “Wrath of the Immortals”, and the “Rules Cyclopedia”, to mention these few.

My role was to plan out the year’s releases and negotiate those with upper management, negotiate components with our marketing managers and purchasing department (since we didn’t own a printing plant, everything had to be farmed out to outside vendors, and cost was a big concern), negotiate rates and deadlines with freelance writers (although some others were dictated by management), give them detailed parameters for their work (general style, direction, and contents, along with some specific themes I wanted to see developed in their work), review their manuscripts and request corrections/updates, supervise in-house or freelance project editors, assist with our production departments to complete page designs, acquire maps and art, put out fires, and review galleys, keylines, blues, and print-ready chromes as much as possible (remember this was twenty years ago, and the technology was quite different than what most of you have become accustomed to), monitor sales, and finally contribute to advertising and other promotional copy for trade catalogs and such. There was a lot of competition among the various creative teams at TSR to secure specific artists. Communication was important to make sure cartographers, illustrators, and cover artists knew what to do, and this often was up to me.

The renowned Rules Cyclopedia

You were the project coordinator for the 1991 Rules Cyclopedia, considered by many as the best complete “RPG in one book” of all time. Can you share with us some memories about the production of that masterpiece?

Yaaaaaargh!

Honestly, this was a crazy assignment. I was blessed to have been able to assign the right people: Aaron Allston to complete the main compilation and development, and Steven Schend as the in-house project editor. Both did marvelously well. Jon Pickens, a staff editor with encyclopedic knowledge of game mechanics and setting up solid rulebooks, made himself available to help Steven with this colossal endeavor. Dori Hein joined in to help keep the project on time. I (vaguely) remember being involved with reviewing everyone’s work and dealing with the graphics department to “try” to get some color into a book absolutely packed with text. It’s all a blur in my mind now. I had to talk with our production and purchasing departments about copying the old chromes from the Trail Maps and reproducing sections inside the book, atlas-style, which had never been done before. Production worked out rather well, with no major problems, which I think is amazing considering the size and complexity of the “Rules Cyclopedia”. I guess we rolled a natural 20 and killed that dragon with one strike. My biggest challenge had been negotiating with upper management for a 300-page rulebook earlier in the year. They kinda looked at me as if I had three eyes. I even got a visit from the VP Finance who wanted to verify that I knew what I was doing, and that I was certain it was going to sell. Not even AD&D, TSR’s golden child, had such a large book back then. It did very well, as any BECMI fan could have predicted. Even today, it’s a favorite among collectors, fetching as much as $170 apiece at auctions. I believe that the “RC” is unique even today as regards the extent of what it provides its owners, and it may very well have singlehandedly extended the entire product line’s lifecycle.

You’re a writer, game designer, world builder. Why do you do this job? What motivates you?

What motivates a rabbit to nibble a carrot? Some things are just in your nature. I’ve always been creative, ever since I was a child, either through painting or writing. I’ve also been a gamer for just about as long. With such a background, it was a foregone conclusion that anything combining the two would be ideal for me. Along the way I developed interests in aerospace, geography, and history during a decade of wargaming. This only added more reasons for doing what I do best. It’s hard work. It can be hugely frustrating at times. But you keep at it, because that’s who you are. Despite all the hardships, there is pleasure in creating something new. There is joy in bringing to life worlds and their people, and in so doing, entertaining readers.

Calidar: In Stranger Skies introduces Bruce Heard’s brand new campaign setting.

Calidar “In Stranger Skies” is your first experience as an “indie” publisher. Was its creation much different from your TSR experience?

Heavens, yes! It was vastly different. During my nearly twenty years in hiatus, the entire universe changed. There was, first of all, the absence of an entire publishing company and its professional, experienced, and knowledgeable people around me to get everything done. Now, I have to rely on myself mostly. Just to get started, you have to have an established readership, people who are interested in who you are and what you can offer them. Without this, you can’t expect to succeed the do-or-die crowd-funding step. The nature of the publishing industry is completely different now, since traditional publishing houses, distributors, and retailers are no longer relevant. Electronic literature and print-on-demand have opened entirely innovative publishing channels and democratized the industry. The technology to produce books is also entirely different, and so are the management and promotion of intellectual property. The nature and expectations of readers have also evolved. After my long absence, I had to relearn absolutely everything from scratch and in a very short time. Addressing freelance contributors as a one-man-indie-publisher also is a challenge compared with how I worked when I ran TSR’s acquisitions. On the other hand, I don’t have an exec looking over my shoulder and telling me I can’t do something. I just have me for this (actually, it’s worse!). The business aspect of a startup venture represents more time and effort on my part than actually creating anything. I can summarize my writing in terms of weeks or merely a few specific months during a year. Most of my time, during and between bouts of writing, focuses on running the business and promoting my work, including telling you about it in this interview.

The next product in the Calidar series will be “Beyond the Skies”, about gods and pantheons. Why this choice, instead of the expected next gazetteer?

It occurred to me that Calidar’s premise relied heavily on aspects of its fantasy divine background. In other words, gods are crucial. Before boldly going ahead and emulating Mystara’s Gazetteers, I needed to work on this topic. It will have a direct impact on every single title in the series, as well as the way players role-play their characters in the game. This was only logical since epic heroes aspire to become deities; the world of the gods therefore had to be defined far more substantially than what CAL1 “In Stranger Skies” offered.

What single piece of advice would you give to a budding game designer?

Pick one:

- Get a real job.

- Learn the business.

- Build a following.

- Do what no one else does.

- Grow a thick skin.

- Embrace what makes you uncomfortable.

- Don’t expect to build Rome in one day.

- Never give up.

- All of the above.

We would like to thank Bruce Heard for his kind participation in this inspiring interview. Stay tuned to Isola Illyon for future updates on his projects!

– Lorenzo Santini –